Lessons from Japan's Football Success for Singapore

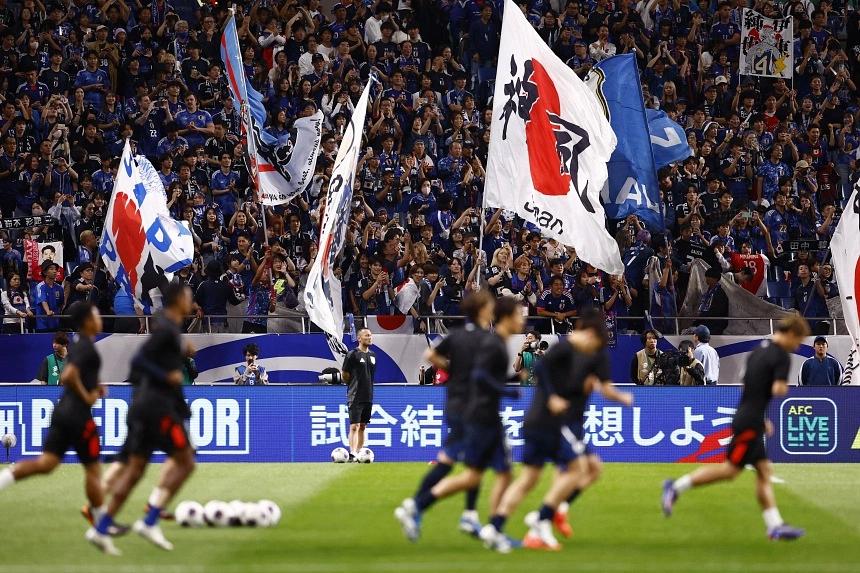

TOKYO – It may be hard to believe now, but just three decades ago, the idea of Japan competing in the World Cup (they did not qualify before 1998) and the Olympics (they missed six consecutive Games from 1972 to 1992) seemed like an impossible dream.

Singapore national football coach Tsutomu Ogura, a former assistant coach with the Japan national and Olympic teams, told The Straits Times: “We were losing to Malaysia and Thailand, and we would lose most of the time to South Korea at various levels (the Samurai Blue were winless in 13 straight games against the Taegeuk Warriors from 1985 to 1993, scoring just five goals).

“We had no professional football league until the J.League started in 1993, when it created full-time opportunities for footballers and we began to make big improvements in every department from there.”

In turn, the thriving J.League has helped propel Japan’s national team to significant heights.

Besides being Asian champions in 2000, 2004 and 2011, they also went from strength to strength at the World Cup, where they stunned Germany and Spain on their seventh straight appearance at Qatar 2022, losing to Croatia in the last 16 only on penalties.

In October, ST followed the Lions’ training camp in Japan and understood from local stakeholders that Japan’s football success is based on starting off on the right foot, foresight and decisiveness when facing challenges, and teamwork – which Singapore football will do well to learn from in its own bid to emerge from the shadows.

THE RISE OF J.LEAGUEThe first edition of the J.League featured 10 teams, with nine owned by large corporations and the other based on a civic club in Shimizu City.

The financial stability allowed teams to sign international stars like England striker Gary Lineker (Nagoya Grampus Eight) and Leonardo (Kashima Antlers), a member of Brazil’s 1994 World Cup-winning squad, which helped improve the league’s quality and attract a wider audience.

After initial success, they faced headwinds as the 1997 Asian financial crisis worsened Japan’s economy crash in the 1990s, and average attendances halved to around 10,000.

Clubs were losing sponsors, which led to Yokohama Flugels having to merge with crosstown rivals Yokohama Marinos, as several sides flirted with bankruptcy.

The Japan Football Association (JFA) responded swiftly, announcing a 100-year vision to have 100 professional football clubs by the league’s centenary in 2093.

It later restructured the J.League to create a second division in 1999, before the third division was launched in 2014.

There are now 20 clubs in each league. Most of them have quality and competitive pitches and the stable of professional referees has grown to 14 main and four assistant referees.

CONNECTING WITH COMMUNITIESTo withstand economic downturns, the J.League encouraged clubs to delve into the communities around them and form partnerships with small local companies, and they all went in with an outreach programme as intense as the football they play.

According to the Sports Marketing Laboratory, a Tokyo-based sports consultation company, one of the philosophies behind the J.League is “each club should have its roots in a specific community”, which is also one of the reasons for the successful promotion of the sport throughout the country.

Nobuhiko Yoshino, management director of five-time J1 League champions and 2024 AFC Champions League finalists Yokohama F. Marinos, shared that other than main sponsors Nissan, they have “200 to 300 big and small companies” backing his club.

“Some of them just want to contribute to society, and we provide them an avenue to do so,” said Yoshino, who added that the sponsorships, along with gate receipts, broadcast fees, transfer fees and merchandise, contributed to their annual operating budget of US$60 million (S$78.75 million), of which half goes to the first team.

The community-based strategy helped bring fans back to the stadiums, with attendances for the 2023 season increased for all three tiers compared to 2022, when the world was emerging from the Covid-19 pandemic.

The average crowd figure rose by 32.6 per cent to 18,993 for J1 clubs. For J2 and J3 sides, the hikes were by 37.6 per cent (to 6,904) and 10.3 per cent (to 3,003) respectively.

YOUTH DEVELOPMENTAmong these are many families, who are now more open to enrol their children into J.League club academies after seeing how clubs take youth development seriously and that there is a future in professional football.

After leading the Tokyo Verdy Under-16s to victory in the Lion City Cup in Singapore on Oct 6, their youth coach Chosun Futemma shared: “Clubs do not coach only football, they also need to improve each player’s personality and mentality.

“Tokyo Verdy think of ‘the spirit of the challenge’ all the time.

“Our purpose is to improve the players to go up to the senior J.League clubs, but we also try to maybe develop the players’ spirit and teach them how to handle themselves, because if not, it will be hard to become a professional player.”

Good mentors are of utmost importance, as Verdy sports director Atsuhiko Ejiri told ST: “We first need to have good coaches, otherwise it doesn’t make sense to have an academy. So, we learn from foreign and senior local coaches and try to develop coaches according to our club philosophy.”

ST also observed that after an Oct 14 friendly with the Lions in Yokohama, the Marinos’ senior players conducted small-group chats with their youth players to foster a sense of identity and inspire them.

All 60 J.League clubs now have academies, and bigger teams like the Marinos boast of a youth set-up with around 3,500 players from fureai (Japanese for friendship) teams for kids to U-12s, U-15s and U-18s.

Naturally this also leads to increased competition, as Yoshino revealed only one or two players from the U-18s make it to the first team each year, while many players retire as early as 25.

The rest, upon graduation from the U-18s, may go on loan to other teams across the three divisions, or play for university teams, which are also of a high level.

The University of Tsukuba knocked out J1 side Machida Zelvia while Japan Soccer College stunned Grampus in the second round of the 2024 Emperor’s Cup.

Notably, Brighton & Hove Albion’s star winger Kaoru Mitoma dropped out of Kawasaki Frontale to join Tsukuba in 2016 before returning to the club in 2018 and making his English Premier League debut in 2022.

VENTURING OVERSEASWith talks of a professional youth league from 2026, the talent pool and quality will increase further as J.League clubs try to impress again in the AFC Champions League after having won it five times since 2007.

As they capture more eyeballs, their top Japanese players are signed by stronger European leagues, while others, latching on to Japan football’s enhanced reputation, try their luck in smaller overseas leagues in search of a launching pad.

In the initial years, many struggled and few, such as Hidetoshi Nakata, adapted.

But in recent years, the likes of Shinji Kagawa and Mitoma proved themselves in the big leagues and the number of Japanese players plying their trade abroad grew from zero to 169 over the last three decades, according to Sports Marketing Laboratory.

Former J.League chairman Mitsuru Murai said: “When the J.League started, it was almost unheard of for Japanese players to go to overseas clubs. They weren’t good enough.

“I’m proud that so many have now gone abroad. And when they return, they also lift the quality of the game in Japan.”

NATIONAL TEAM SUCCESSAt the last World Cup, 19 of the 26 players were based in seven European countries – Germany, Spain, England, France, Portugal, Belgium and Scotland – while three others had prior experience playing in Europe.

Being able to survive in the European leagues gave them the confidence and know-how to beat Germany and Spain, and making it to the knockout rounds for the fourth time gave them the belief that Japan belong among the big boys.

They are now No. 16 in the world, a far cry from being 54th at the end of 2014.

This led J.League chairman Yoshikazu Nonomura to declare that “football culture has taken root in Japan”.

He added: “When the league began, I think a lot of people thought of it as just flashy entertainment.

“Now 30 years have passed, and I think we are getting close to the real J.League that we were aiming for.”

WHAT SINGAPORE CAN LEARNWhile no two ecosystems are the same, and Singapore football does face constraints in terms of land and population size, with societal and developmental differences that prevent “wholesale” replication, Football Association of Singapore president Bernard Tan felt there are lessons to be learnt from the Japan success story.

He cited how the Japanese players look after their bodies, turn up for training earlier to do their own warmups and stay back an hour to work on their strengths and shortcomings, so that they “take so much more from each session”.

He said: “What is difficult to replicate – and this is what makes the competitive difference – is football culture.

“The Japanese have a competitive mindset and discipline that drives development to a very high level from a very young age.”

Role models like Arsenal’s Takehiro Tomiyasu and Liverpool’s Wataru Endo who have “broken the glass ceiling” to play in top European leagues help to inspire future generations to take football seriously, but many more jigsaw pieces – such as corporate support – also need to fall in place for a national team to succeed.

Tan added: “We also require our coaches to not see coaching as just a job, but a mission to develop world-beaters.

“While we can copy the facilities, infrastructure and training plan, what we really need to do is to work on the softer elements to inspire a generation so that they can aspire to be the best in the world.”

RELATED STORIES

LATEST NEWS